South Chemist Working to Find Invasive Citrus Killers

Posted on July 10, 2018

If you have a citrus tree in your back yard, or you grow citrus trees for a living, or you just enjoy fresh, locally grown citrus fruits, there’s a tiny bug that is working to ruin your day.

The little critter is the Asian citrus psyllid. And it doesn’t travel alone. It hops from leaf to leaf on citrus trees, carrying with it a bacterium which infects the tree with Huanglongbing (HLB, or loosely translated, “yellow dragon disease”). HLB is a citrus-greening disease, and it results in stunted growth, inedible fruit and, ultimately, the death of the tree in 2-to-5 years. The diseased tree also acts as a supply of bacteria for additional infestations as the insects move.

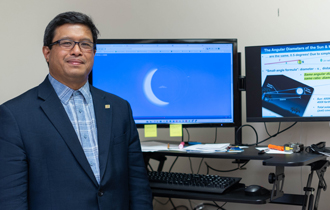

You ask Dr. David Battiste about it, and the University of South Alabama assistant professor of chemistry doesn’t mince words.

“Citrus greening is the most serious disease threat to the citrus-growing industry worldwide, due to its complexity, destructiveness and resistance to management.”

According to Battiste, citrus greening was first observed more than a hundred years ago in Asia. But in our global village, things have a way of getting around, and last year the citrus-greening disease made its way to citrus trees on Dauphin Island in Mobile County and Bear Point in Baldwin County.

“The problem with this citrus disease is that host plants are grown in many backyards throughout the region, not just in nurseries or in commercial groves, and the disease is hard to detect,” Battiste said.

Tackling a worldwide problem can be overwhelming. But if you can’t save all the citrus trees in the world at once, Battiste believes you definitely can try to save citrus trees in southwest Alabama. So he, along with the Gulf Coast Resource Conservation & Development Council and the Alabama Department of Agriculture and Industries (ADAI), has put together a team, and what a team it is.

“He has ‘deputized’ participants through the public school system; specifically, Alabama Science in Motion teacher Jessica Owens, numerous high school students and their teachers on this issue,” said Dr. David Forbes, professor and chair of chemistry at South. The teachers include Felicia Fawcett, Daphne; Amanda Jennings, Fairhope; Alisha Perkins, Bryant and Sonya Scott, Mary G. Montgomery.

“We are trying to exponentially increase our ability to detect the psyllid by increasing participation of students and teachers,” Battiste added. His volunteers have dispersed throughout Mobile and Baldwin counties to try and find the bug and act as an early warning system so the disease can be managed.

But how?

In more than 60 locations in the two-county area, student and teacher volunteers this spring and summer have been armed with special lime-green sticky traps, coupled with a chemical pheromone pouch which attracts the bugs. (You’d be lucky to see and catch the psyllid, since they’re only about three millimeters long. And they can jump. And fly.) The volunteers hang one or two traps in each tree. The traps are covered with a sticky substance that, once on it, any insect (including the psyllid) is stuck. After recovery from the tree, the trap is first inspected by the students with a hand lens and then returned to Battiste to be inspected with a stereomicroscope.

That’s the plan, but there’s been one small problem.

“We have not found psyllids while our traps have been out since January,” Battiste admitted. But he says the prime time to catch psyllids is August through November, so the battle is really just beginning.

He and his team have traps hanging in four trees on Dauphin Island because that’s one of the infection sites. And if the Battiste team is fortunate enough to capture one of the psyllids, then things get really involved.

“If psyllids are found, both psyllids and trees can be tested for the bacterium. If diseased trees are found, the ADAI has to inspect every citrus tree within five miles of that tree…a very difficult task,” Battiste said. “Cooperation of home owners is needed but this is an extraordinarily slow process and lots of psyllids have time to infect other trees. If we can use the psyllid traps as sentinels in the early warning system, then we can better manage the spread of this disease. Spraying for psyllids and eliminating infected trees buys us time while plant researchers work to find a cure or develop resistant plants.”

No cure exists yet for infected citrus trees, and no citrus tree varieties are resistant, so the key is to detect and kill the psyllids quickly.

“With rapid, extensive and timely public information, as well as a positive outlook of the importance of the project by the whole citizenry, all Gulf Coast counties in Alabama may be able to mitigate the devastating loss of citrus trees as experienced in Florida, where home owners and large groves have suffered 70 percent losses of citrus trees,” Battiste said.

As head of USA’s Pheromone Center, Battiste also has an ulterior motive for helping out. “Our hope is to interest students in how chemistry (e.g., pheromones) helps detect these issues we face. There are more bad invasive insects, like kudzu bugs and brown marmorated stink bugs, heading our way. Thus, we would like our local students to see the relevance of what chemistry does for better living.”

Battiste wants to expand the program to include Clarke, Monroe and Washington counties, while recruiting more volunteers for Mobile and Baldwin counties. If you’re interested in becoming one of Battiste’s citrus soldiers, email him at chemistry@southalabama.edu.

Archive Search

Latest University News

-

Case Study

South engineering students tackle a senior project to design a battery...

April 16, 2024 -

Rachmaninoff and Research

A South engineering and music student wins a Goldwater Scholarship for...

April 8, 2024 -

5 Things to Know About the Solar Eclipse

South physicist Dr. Albert A. Gapud gives a primer on next week's...

April 2, 2024 -

Super Commuters

One crosses the equator line, the other eight time zones. Both Danny N...

March 25, 2024