Searching for the Smallest Known Thing

Posted on November 22, 2017

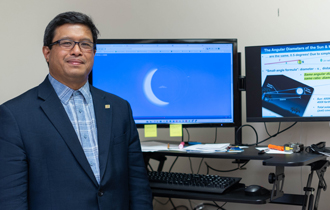

Inside a physics laboratory at the University of South Alabama, Dr. Martin Frank and his students regularly search for something they can see only with the help of computers and a multi-million dollar particle accelerator that begins outside Chicago and ends inside a particle detector in northern Minnesota.

As Frank, an experimental particle physicist, and his students monitor their wall of computers, a nearby screen displays a similar laboratory, with professors and students, inside another university located elsewhere in the United States. About 200 researchers are connecting online in the NOvA Project to learn as much as possible about neutrinos — the most abundant particles in the universe, a billion times more common than the particles that make up stars, planets and even people. In fact, tens of thousands of them are passing through your body right now. Frank is USA’s lead researcher for NOvA.

On the lab’s computer screens, neutrinos are recognized only as a flash of light, the result of one colliding with a proton or neutron, something that happens infrequently. That’s because a really huge amount of space lies between neutrinos and the larger elements. In other words, among a trio of things you cannot see, the neutrino is the smallest known thing.

“Most people know what protons and neutrons are, but neutrinos are much, much smaller than those,” Frank explained. “Their existence was theorized for many years, then in 1956 it was confirmed, but we are still learning about them. The theoretical physicists come up with a hypothesis about what’s there, but it’s the experimental physicists who confirm things exist, then research to determine what those things actually do.”

A comment about Frank being a real-life version of television character Sheldon Cooper from the popular sitcom “The Big Bang Theory” draws a hearty laugh.

“I’ve heard similar comments before, but I’ve never watched that show,” Frank said. “But, if it’s about physicists, it can’t be all bad.”

Before coming to South in August, 2016, Frank was a postdoctoral research scientist at the University of Virginia, assigned to Fermilab, the government site outside of Chicago where the neutrinos are now beginning their research journey. It was the largest and most powerful particle accelerator in the world before the CERN Large Hadron Collider began operation in Europe.

Next year, Frank and his colleagues will publish their first research analysis on what they have learned so far during the NOvA Project. In the meantime, Frank is mum about the paper’s contents.

“It’s part of our collaboration agreement that we don’t discuss details with anyone outside the research project,” Frank said.

However, as he and his students watch the neutrinos, he’s also interested in something else – a magnetic monopole, a hypothetical elementary particle that is isolated with only one magnetic pole.

“Humanity has wondered about the existence of a singular magnetic pole for centuries,” Frank explained. “Technically, you can’t prove something that isn’t there, but a non-observation is as useful as an observation.”

For junior physics major Erriel Milliner, who is from Birmingham, her time inside the lab working under Frank’s direction for this research project is more than she expected.

“I originally wanted to be an aerospace engineer, but I didn’t want to leave South to take some courses I needed, so I changed my major to physics, and I’m glad I did,” she said. “I like the atmosphere and the people here. Plus, the class sizes are really nice. I’m getting opportunities to work under Dr. Frank I probably wouldn’t have at other places.”

Fellow student Paul White of Gulf Shores agrees. “When I graduate in 2020, this will be my second degree from South. My first one was in graphic design because I was trying to get a degree as quickly as possible. I came back because physics has always fascinated me.”

Both Milliner and White agree physics satisfies their urge for a career that’s challenging and interesting. Each hopes to eventually earn a doctorate, then work for a government laboratory.

“Although you may not be able to see everything, something is always happening with physics,” Frank said. “It’s never boring.”

Archive Search

Latest University News

-

Case Study

South engineering students tackle a senior project to design a battery...

April 16, 2024 -

Rachmaninoff and Research

A South engineering and music student wins a Goldwater Scholarship for...

April 8, 2024 -

5 Things to Know About the Solar Eclipse

South physicist Dr. Albert A. Gapud gives a primer on next week's...

April 2, 2024 -

Super Commuters

One crosses the equator line, the other eight time zones. Both Danny N...

March 25, 2024