Mobile Unearthed

Posted on June 6, 2025 by Alumni

Spanning the history of Mobile Bay, the I-10 Mobile River Bridge Archaeology Project

is the largest undertaking the USA Center for Archaeological Studies has ever conducted.

Partnering with Wiregrass Archaeological Consulting, the team excavated 15 sites along

the new bridge route from November 2021 to June 2023, uncovering a trove of artifacts,

including pottery. The team painstakingly examined each fragile piece of pottery they

found, unveiling, one by one, significant fragments of local history.

“Ceramics are one of our best sources of information at an

archaeological site,” says Rachel Hines, the project’s public outreach coordinator.

Because designs and methods of making pottery change over time, these items — even

tiny fragments — can reliably indicate a site’s age and provide valuable insight into

trade networks, international connections, lifestyles and social classes of their

times.

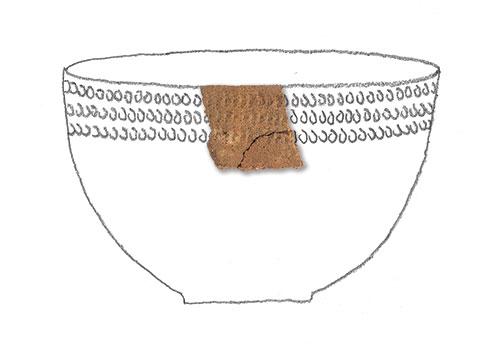

PHOTOGRAPHS of excavated

pottery sherds are shown

within the context of the

full piece they might have

come from.

BAYOU LA BATRE STAMPED

POTTERY SHERD

(2,650-1,800 years ago)

The oldest artifact identified by the project, this fragment is from a vessel that

was stamped while the clay was wet, likely with a scallop shell edge, making the design

easy to replicate. Excavated near Virginia Street, this type of pottery was first

identified in the 1950s in the south Mobile County city of Bayou La Batre.

PUEBLA POLYCHROME MAJOLICA CERAMIC SHERDS

(1650-1725)

The colorful majolica, a tin-glazed earthenware ceramic, was made in Mexico until the 1800s and often shaped into deep brimmed plates or bowls. At that time, Mexico and Mobile were both part of New Spain. These sherds were found just south of the Spanish settlement in Mobile, which was located near Fort Conde.

ST. CLOUD FAIENCE PLATE

(1675-1766)

French faience is often found on French colonial sites in the Southeastern United States established before 1800. The nearly complete plate, an extremely uncommon find, was excavated south of downtown Mobile inside a barrel well. Such wells were often used for trash after they ran dry.

COMMON CABLE PEARLWARE BOWL

(1790-1820)

Pearlware, made in England around the turn of the 19th century, has a distinct blue-tinted glaze. This cabled, finger-painted bowl, found near the corner of Royal and Madison streets downtown, gives us a glimpse of life during a period of scarce archival records just before Mobile became part of the United States in 1813.

#SoMobile

During the I-10 excavation project, the team discovered items that were a part of

the city’s identity, such as an old Mardi Gras pin and this token for a trip on a

local streetcar.

STREETCAR TOKEN

(1916)

By 1908, the Mobile Light and Railroad Co. had 50 miles of streetcar track along 20 different lines.

This token was found behind the former 906 S. Franklin Street, the home of the Owens family. The city’s first electric streetcars emerged in the 1890s and were prevalent until 1940, when buses replaced them.

EDGE-MOLDED WHITEWARE PLATE

(1943)

Recently produced pottery, like

this, often has a maker’s mark,

which provides more information

about the manufacturer. Homer

Laughlin produced this pottery;

its maker’s mark indicates that

it was made in May 1943. It was

found on Franklin Street near

the former homes of the McCall

and Sanders families, who were

working-class African Americans: Sterling McCall worked at the

shipyards, and Maggie Sanders

was a maid at the Battle House

Hotel.

Click here to view the current issue of South Magazine