Prepare for Homegrown Hurricanes

Posted on May 31, 2016

It’s summertime, and the living is easy, unless you’re a hurricane expert like Dr. Keith Blackwell and his meteorology colleagues at the University of South Alabama.

Almost 11 years have passed since Hurricane Katrina struck the northern Gulf of Mexico, but hurricane season officially begins June 1, and the associate professor of meteorology is already concerned about possible increases in tropical storm activity.

“We meteorologists are going to have to be a little more on our toes this year, compared to last year, with storms forming a little closer to the United States,” Blackwell said. “Of course, we usually are vigilant here on the Gulf Coast, but with El Niño going away and La Niña returning, we want to pay a little more attention to the Caribbean rather than areas off the coast of Africa.

Traditionally, 85 percent of U.S. hurricanes begin as upper air disturbances off the coast of Africa – hurricanes Camille in 1969, Frederic in 1979, Elena in 1985, Georges in 1998 and Ivan in 2004. However, one of the most disastrous storms to strike the U.S., Katrina in 2005, formed over the Bahamas.

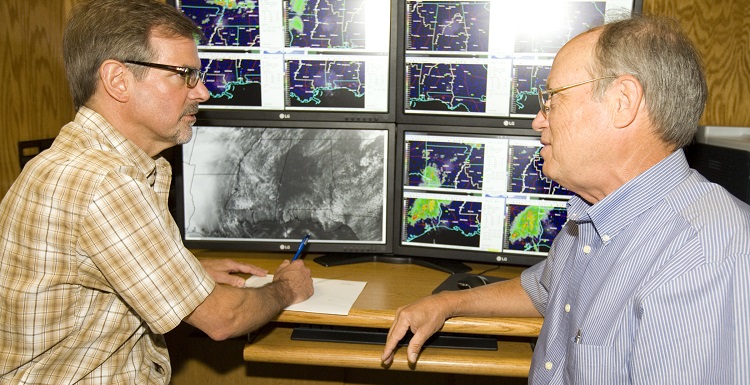

Blackwell, an internationally recognized expert in hurricane eyewalls, is one of several meteorology professors at South whose research focuses on hurricanes. The Coastal Weather Research Center, located inside the Mitchell Center, is operated by USA meteorologists who provide daily weather reports to more than 100 business clients nationwide. Until hurricane season ends in November, Blackwell and his colleagues will be in close contact with the Coastal Weather Research Center where wall-to-wall computer monitors display an array of incoming data for rapid interpretation to these businesses, many of them dependent on good weather in the Gulf of Mexico for their economic survival.

“Last hurricane season, we had a significant suppression of activity in the Gulf and the Caribbean Sea because of El Nino’s excessively strong vertical wind shear, which was one of the strongest on record since the beginning of the satellite era back in the 1970s,” Blackwell explained. “It was so outrageously strong that nothing could survive that.”

El Niño and La Niña are the ying and yang of upper atmospheric steering currents. El Niño events are associated with a warming of the eastern tropical Pacific, while La Niña events are the reverse, resulting in a sustained cooling of these same areas. The recent strong El Niño resulted in warm and rainy winters for the northern Gulf.

Blackwell said the area will be back in La Niña by the end of the summer.

“That will help to make our storms more homegrown rather than from afar, and we need to also keep a close eye on possible formations off areas like the coast of Georgia,” he said.

For example, over Memorial Day weekend Tropical Storm Bonnie became the second named Atlantic tropical system of 2016. The storm made landfall as a tropical depression just east of Charleston, S.C.

Pete McCarty, director of the Coastal Weather Research Center, said the expected increase in storm activity will likely add to their client list now that hurricane season is here.

“We have a year-round client list, but we always add additional clients once the season is here. There are an amazing number of businesses and industries that could be impacted negatively if a storm enters the Gulf – everything from oil companies that have oil rigs out there to companies that trade in oil stocks. Then, there are chemical and paper companies, as well as electrical providers, all along the region,” said McCarty, a USA graduate who began working at the center in 1988. “If a storm enters the Gulf, we are prepared to run here 24/7 to keep our clients informed.”

For the first several weeks of hurricane season, Blackwell will be at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab, teaching a hurricane course for marine biologists. He calls it “a hurricane class for laymen” because these students are taking his course as an elective. However, the professor is adamant that they learn how hurricanes form, move, and, finally, alter lives, landscape and land when they come ashore.

“There’s not a better place in the United States to teach about hurricanes than Dauphin Island. One of their first homework assignments is to drive around the east end of the island, look at older pine trees, then come back and tell me which way they are leaning,” he said. “After they tell me all those trees are leaning to the northwest, I challenge them to learn why that is, the storms that caused that to happen.”

The strongest and most dangerous winds inside a hurricane are located in the northeast quadrant of the storm. Since the eyewalls of both Hurricane Frederic in 1979 and Hurricane Elena in 1985 passed over Dauphin Island, Blackwell said they permanently bent the trees. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 pushed 100 mph winds across the island. However, its eyewall made landfall to the west, near the Mississippi/Louisiana state line.

“The last week of our hurricane class, we take a boat trip around the other side of Dauphin Island, and I show them what the land used to look like 10 to 15 years ago and how the island has changed with each storm,” Blackwell said. “One of the most interesting things has been the merger of Sand Island with Dauphin Island. The two merged right where the public pier is, and that is why the public pier is now on dry land. But, Sand Island is getting shorter and shorter, so in a few years, Sand Island probably won’t be there, and the pier will be back in water again.”

Besides Blackwell’s summer class, South’s meteorology students learn quickly that studying hurricanes on the northern Gulf Coast is often up close and personal in many ways. On May 19, several meteorology students met members of the famed Hurricane Hunters, based at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Miss., and toured their airplanes during the 2016 Gulf Coast Awareness Tour, sponsored by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the U.S. Air Force Reserves. The Hurricane Hunters fly into tropical systems to collect data, which is used to inform and warn coastal residents as a system approaches land.

Andrew Murray, instructor of meteorology, attended and distributed hurricane preparedness literature, as well as information about studying meteorology at USA, on behalf of the department of meteorology.

“This was the first time the tour had been in Mobile since 1999, and it was a great opportunity for the public as well as our students,” Murray said.

Senior Alysa Carsley, 21, a broadcast meteorology major from Philadelphia, was one of the students who learned what it’s like to fly into a hurricane.

“It was very interesting and eye-opening to see what they do and to see how small their plane is on the inside,” Alysa said. “But, the most interesting thing was how they nosedive many thousands of feet into the hurricane, and they are completely fine. That blew my mind!”

Carsley selected South for its meteorology program, low teacher-to-student ratio and “after 18 years of shoveling snow and ice,” she wanted to move to the Southeast.

“I love South because I’m learning so much more because of the small class size and personal interaction with my teachers,” Carsley said.

Although she experienced Hurricane Sandy when it hit the Atlantic Coast in 2012, she admits that she views hurricanes differently now after three years of meteorology studies.

“I definitely don’t look forward to a hurricane because I know how awful they can be,” she explained. “But, experiencing it as a meteorologist and learning about it from my meteorology professors would be an interesting experience.”