Shipbuilders Local 18 Labor Union

Posted on November 24, 2025 by Marie Jansen

The industrial revolution brought about new social and economic impacts, and many national labor unions formed as a response around the turn of the 20th century. For example, the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America, or IUMSWA, was formed in 1933. They advocated for better wages, safer working conditions, and a 40-hour work week for all workers associated with the American shipbuilding industry. They also pushed for health insurance, sick days, paid vacations, and retirement pensions, among other benefits.

IUMSWA became a very large and powerful workers’ organization along the East Coast, particularly in naval shipyards in northeastern port cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. It was one of the first unions to become fully integrated, representing all levels of workers from highly skilled to unskilled. At its height in the 1950s and 1960s, there were more than 100 union chapters.

IUMSWA Local 18 Union Hall in Mobile in 1988. Mobile Historical Development Commission, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

Mobile’s Local 18 chapter represented all skill levels of workers at the Alabama Dry Dock & Shipbuilding Company (ADDSCO). ADDSCO was established in 1916 and thrived during United States involvement in World War I, with 4,000 employees producing and repairing war ships, barges, and minesweepers for the US Navy. During World War II, ADDSCO grew with 36,000 workers building and refurbishing many cargo vessels for naval combat. However, ADDSCO wasn’t giving equal treatment to its employees.

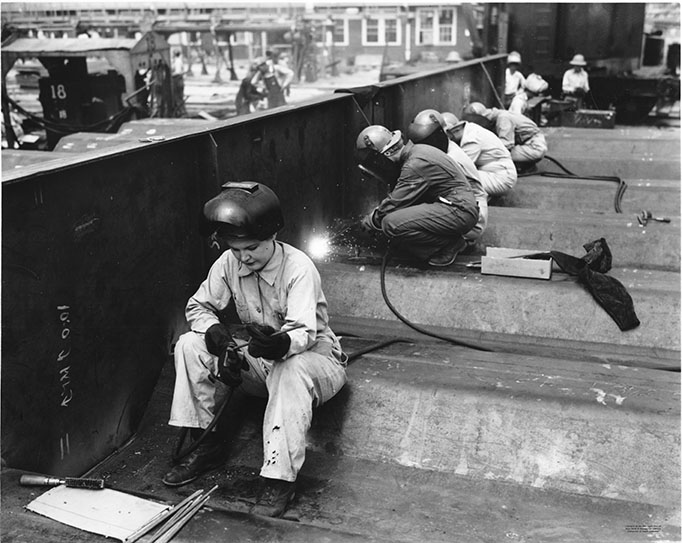

In 1941, local activist and member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) John LeFlore took up the cause of Black workers in the shipbuilding industry in reaction to continued discriminatory employment practices. ADDSCO was hiring and training white women for skilled wartime production jobs such as welding, while denying similar training to their Black employees for those jobs.

Women welders at work in 1945. Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

In 1942, the Fair Employment Practices Committee set up by President Roosevelt had ordered for war industries to desegregate and promote at least some African American laborers to skilled positions. For almost a year, ADDSCO refused this order and maintained segregated work forces, resulting in a race riot. Eventually, ADDSCO gave in to the federal mandate and to pressure from integrated unions such as Shipbuilders Local 18. After the war, the company continued to operate as a ship repair facility with only a few thousand workers.

ADDSCO welders in 1940. Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Collection, The Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama.

Local 18 was involved in local, regional, national, and even international social

and political issues, aligning with Dr. Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign.

Local 18 supported the family of Michael Donald, a young African American who was

murdered and lynched in Mobile in 1981 and demanded the arrest and prosecution of

the white men accused of the crime. When ADDSCO wrongfully fired Pauline Crawford,

the first African American woman hired as a pipe fitter, Local 18 fought against her

firing and were successful. They also supported food banks and the local chapter of

the American

Red Cross and United Fund.

In the 1980s, Local 18 fought for workers after the increasing occurrence of job-related illnesses caused by their exposure to toxic chemicals like asbestos. One Local 18 officer presented his concerns about workplace health issues at ADDSCO at a National Convention of IUMSWA in 1988, which led to resolutions concerning Occupational Disease Prevention and National Health Care Plans.

Local 18 fought for employees at ADDSCO until the shipyard closed, though they took a stand in many social and political issues spanning from local to international affairs. They operated out of the Union Hall building, located at 300 South Royal Street in Mobile. The structure was recorded as part of the I-10 Mobile River Bridge Archaeology Project. Although Union Hall was demolished, its history offers insight into Local 18’s endeavors, providing a deeper understanding of Mobile’s past.

This blog post was adapted from the report “Local 18 Union Hall” by Bonnie Gums and written by Marie Jansen, a Communications graduate from the University of South Alabama.